Salt Lane, Coventry

Archaeological Excavations at Salt Lane Car Park Coventry

overview

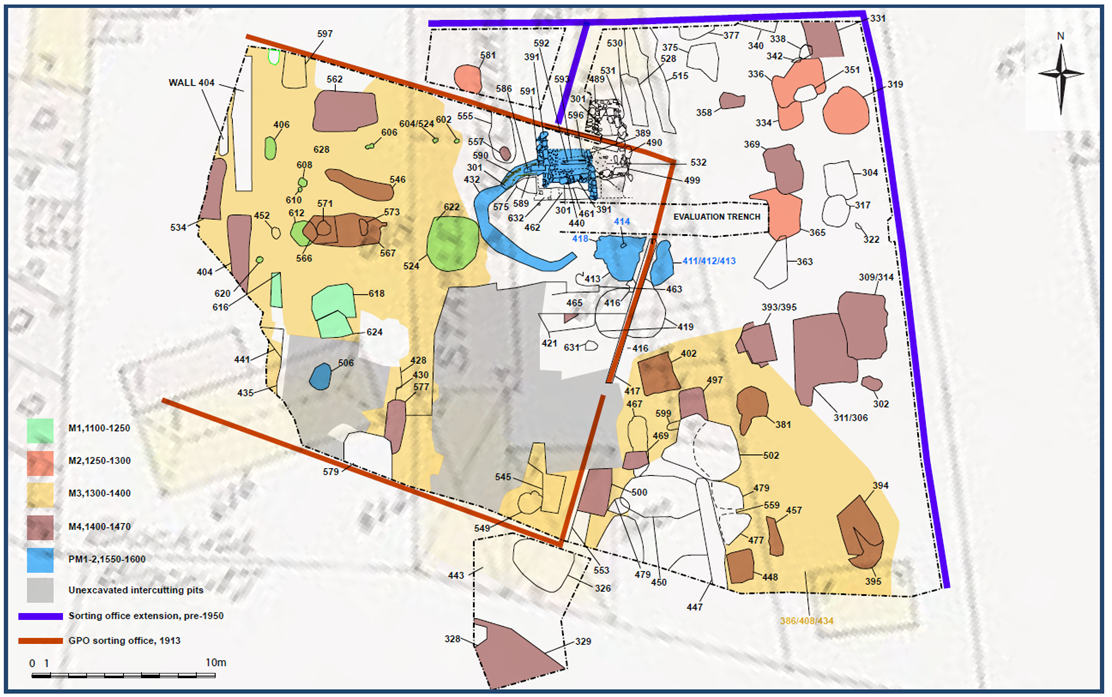

Archaeological excavations were undertaken in 2019 on behalf of Coventry City Council prior to and alongside the construction of a new multi-storey car park. The work followed a trial trench evaluation which demonstrated that, despite modern truncation, well preserved medieval and post-medieval archaeological deposits were present across the site. The archaeological excavation concentrated on an area of c.875 square meters over parts of two medieval burgage plots (properties) divided by a ditched boundary.

On ceramic grounds, the earliest remains excavated on Salt Lane date from the 12th-13th centuries. Coventry during this period was a town which is still unfamiliar even to many historians and archaeologists. It was at that time smaller than nearby Warwick and had strong midland links, through the Earl of Chester and the Benedictine Priory, but if it enjoyed any international renown, it has not come down to us. Thirteenth-century Coventry was a place of growing aspiration, with over another century to go before it achieved the status of a city. By 1279 it had begun to attract many people from the villages and countryside as is evidenced by the Warwickshire village-surnames to be found in the Hundred Rolls for the city.

Prominent buildings comprised its vast, newly-completed Benedictine Cathedral Priory of St Mary (probably begun in the early 12th century and consecrated in c1224), and the still-diminutive St Michael’s and Holy Trinity, both simple two-cell parish churches, each probably without either tower or spire.

Thus the isolated post-hole building which characterises the earliest phase of occupation on the site, but which lacks contemporary floor surfaces, may fit into the purview of any number of small-scale industries, or even may simply be an urban paddock, for the corralling of livestock, horses perhaps. Set well back from any frontage, it is unlikely to have been a domestic dwelling, although it may have stood in support of a frontage building subsequently replaced.

In the second half of the 13th century there does appear to have been some pit-digging on the Salt Lane site, although in no great density. Whether the pits dug were for the extraction of clay and sandstone or for the disposal of waste, the backfilling of those pits with waste remains their principal characteristic, as is the case with most such excavations in the medieval city.

By the early 15th century, there is sufficient documentary background in existence to be certain that the individual plots were separated one from another, by hedge, ditch or fence, or any combination of these, although it remains true that no contemporary boundary features survive to show for this. It is in fact the superimposition of the later (post-medieval), mapped boundaries onto the site which indicates that in this late medieval period, the plethora of mainly pits do seem for the most part to carefully respect north-south lines on the map which would not be depicted by cartographers until the idle of the 18th century. It is therefore in this phase that one can first of all truly assign with confidence finds to a western plot (B) and an eastern plot (C), and even one or two possible boundary features which may or may not demark the westernmost plot A. It is of course during this period that for the first time there are good documents which name the plots and indicate who owned them, who tenanted them and to a large extent suggest what trades were plied therein.

The pottery from the pits associated with the former frontage shows that during the period of the inns, material was being deposited in roughly the period 1400-1470, before the debris supply dried up, either because it was deposited elsewhere, carted away to a town muckhill (such as Graffery Muckhill, on Greyfriars Green), or occasionally because a plot became run-down or was abandoned (which we know did not happen here). It is most likely that with a growing need to use more of the rear plot, and make it safe for horses, the inn tamped down the ground over the former pitting, or even metalled it, and their refuse went mostly elsewhere. There is also the possibility that 19th and 20th-century redevelopment reduced any post-medieval build-up in ground levels sufficiently to scrape away any later pits. Because of this, later pit-digging evidence on this site is and will remain equivocal.

Certainly the pits produce none of the ceramic type fossils of the late 15th and 16th centuries, usually found all over Coventry, such as domestic Cistercian Wares and the rustic-looking continental imports for drinking ale like firstly Raeren tankards and then Siegburg and Frechen types. The dateable refuse supply simply ends in the later 15th century, perhaps not much later than c1470.

A garden of an inn which dates back to at least the 14th century, was uncovered, known as Green’s Inn from the family who ran it. By 1572 the inn, probably rebuilt, had become known as The White Bear, although at the end it had been re-named The Craven Arms. It stood well into the 20th century and was for a time the premier coaching-inn of the city, with stabling for 40 horses. It is perhaps no surprise that between the horses, with saddlers living next door, finds include considerable horse-tackle, such as a fine articulated bit.

The inn would have put up visitors to the city of every class, from tradesmen to gentry. It may be one of them who lost a well-worn but finely-decorated sword scabbard, with evidence in its wear that the owner also used it to hide an additional dagger, both accessories which betoken that theirs could be a very violent society indeed.

From the 13th century documents show that an adjacent Little Park Street plot supported a scabbard-making cottage industry, so the wearer might have come to be measured-up for a new one, just as he discarded his worn-out example.

In the rear yard of the White Bear of the late sixteenth century and early seventeenth century stood a small building set on stone foundations with a brick floor. Nothing about its remains gives a clue as to its superstructure, which may well have been timber-framed, or its purpose, since there were no finds related to it. It may have been little more than a shed. It is more than likely however, that the water which ran off its roof in a rainstorm was needed to replenish the large stone-lined pit which lay next door to it. With a wicker-lined channel and planked base leading into it and an overflow channel opposite off it, the pit was distinctive in that it supported upright driven stakes, some probably themselves wickered to form racks in a pit which was designed to hold water to some extent, be replenished by water from the nearby roof and then drained off as necessary Again, no finds indicate that this pit enjoyed any use previously encountered in the city’s archaeology. However it seems likely (if perhaps ultimately unprovable) that this formed a wheel-wash for cart traffic which stayed at the White Bear.

While no wheel-parts have survived at the White Bear Inn to confirm this suggestion, it is surely reasonable to suggest that while horses were undoubtedly cared for, wheeled traffic needed at least as much attention as a result of wear. A wagon with a split felloe (wheel-rim) or loose strake (iron tyre) was no more use than a lame or ill-treated horse. In a back yard where dozens of horses and carts and carriages passed through each week, at least some of each would be worse for wear on any one day. The inn which wished to garner a regular clientele would be the one which provided the most extensive service. With generations of sadlers next door (to both sides) and blacksmiths always only a short walk away, the added ability to ‘service’ carts on the premises would have made the White Bear a reassuring prospect for the late medieval traveller

Written by Iain Soden

With acknowledgment to -

Paul Blinkhorn, Sheila HamiltonDyer, Tora Hylton, David Dungworth, Michael J. Allen, Alan Clapham, Quita Mould & Michael Bamforth

Post excavation report can be found with reference -

Rann, C., ed 2020 Archaeological Excavations at Salt Lane Car Park, Coventry: Post Excavation Assessment, Archaeology Warwickshire Report 2061